Our water cycle is well understood – something taught at school and then possibly forgotten by many. While we tend to simplify and compartmentalise the water cycle in our built environment to provide a line of sight on its management, Three Waters is, in reality, One Water – connected and circular in nature.

Through our built and natural infrastructure, we have controlled, abstracted, treated, consumed, then discharged this water for our benefit. Our communities expect that the water they consume and recreate will be available, safe, and culturally appropriate. Unfortunately, that does not hold true all the time in New Zealand.

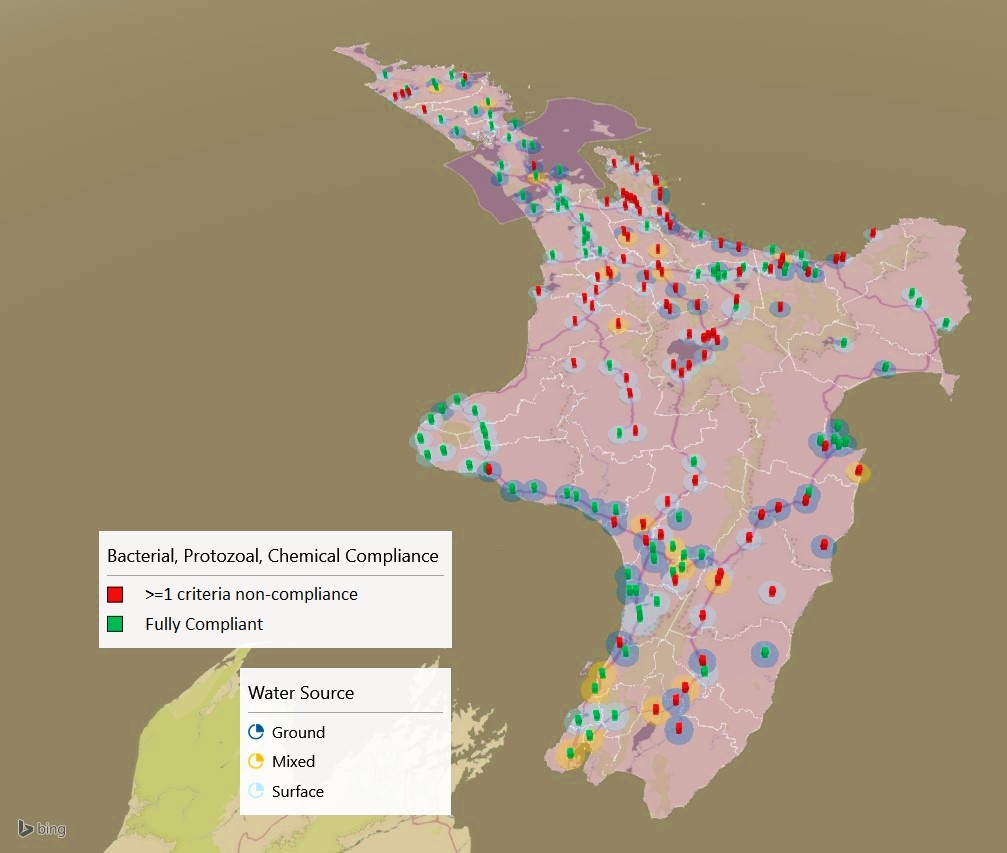

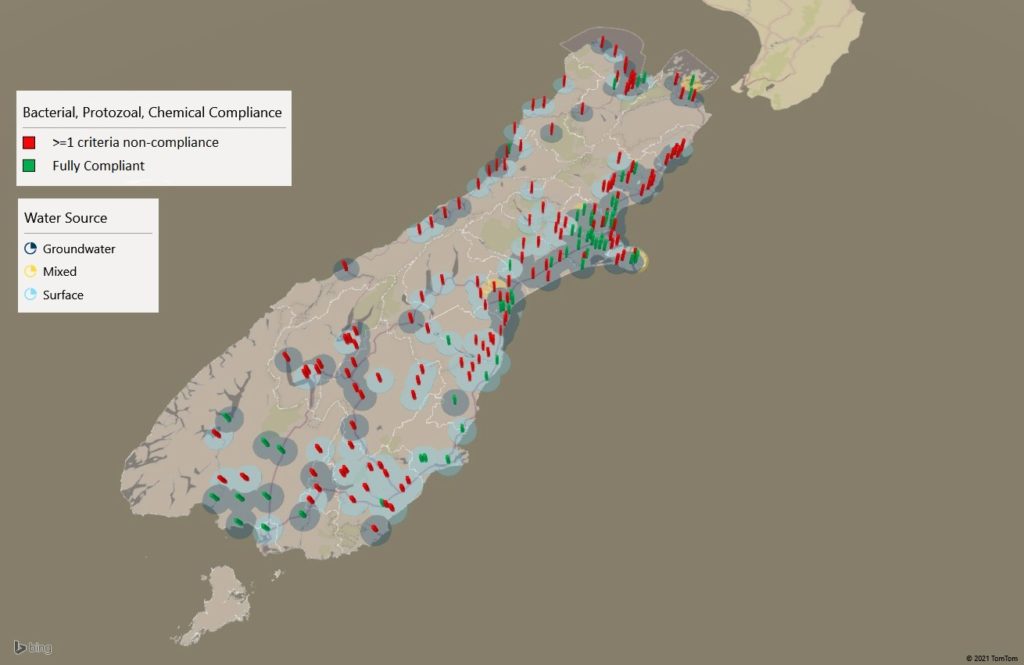

A look at 2019/20 nationally reported Registered Water Supplies Compliance data (see images) across the country gives a stark reminder of the difficulty in suppliers achieving compliance, particularly for quality criteria.

Non-compliance in some cases could be not following the process or taking an insufficient number of samples. However, it could also be that a public health risk is present or a system has failed, so a boil water notice is required.

Water New Zealand technical manager Noel Roberts has noted that with the Water Services Act now in force, Clause 21, “Duty to supply safe drinking water”, means that taking a compliance-only approach to water supply and along with meeting minimum monitoring requirements won’t be accepted. A more vigilant risk management approach is required.

Digital water: Simplicity from complexity

Meeting these new goals may appear daunting, unachievable, and unforgiving. Turning to and embedding digital water is part of the potential solution mix. That is, technologies that allow coordinated information-driven decision making, planning and financing at a one water scale.

Digital water’s success will lie in being digitally agile, with skilled people, streamlined approaches, and risk-based processes and platforms. Systemising as many processes as possible will be needed to balance the shortage of skilled people.

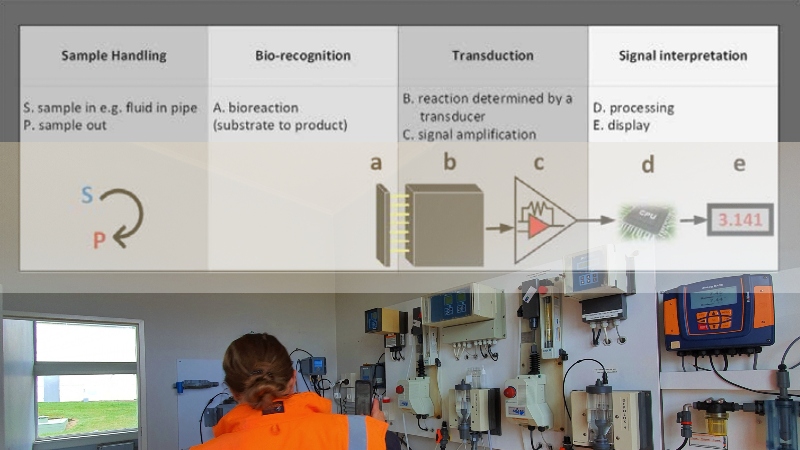

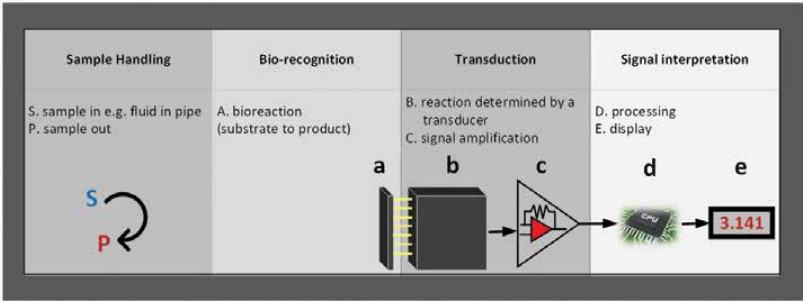

Biological sensors, or biosensors, are one stream of emerging technologies that hold significant potential to detect and alert us about contaminants such as metals, bacterium, viruses, and chemicals, in near real-time. You may already be familiar with commodity level biosensors such as the home pregnancy test kit and ‘in arm’ glucose (insulin) monitoring unit.

Biosensors are analytical devices. An analyte or specific target substance, e.g. virus, produces an electrical response when binding with a specific substance media. A transducer converts the binding event into a measurable electrical signal which is then amplified and digitally displayed.

There are, however, a number of challenges in taking biosensors from the laboratory to the commercial (commodity) level.

The major technical challenges in developing biosensors for virus detection in water and wastewater include relatively low virus concentrations, small particle size, naturally occurring inhibitory substances, and their unique structure requiring exact matching with the recognition substance.

Significant effort is being put into biosensor development for Covid-19 rapid detection in wastewater.

Further, imagine a future where every household water connection has an embedded biosensor-communications system monitoring water quality.

This is connected to a stop valve, which is activated if the indicator virus, chemical or metal is detected. An alert is also sent to the water supplier and property owner for immediate action.

Acknowledgement: This article was published in the Water New Zealand Journal, November/December 2021 Edition.